“There has always been infighting between two schools of thought when it comes to art. Some people place a higher value on a film’s ethics and representation— those we’ll call moralists — and some place higher value on a quality Vladimir Nabokov once called “aesthetic bliss” — those we’ll call formalists… This philosophical rivalry isn’t new to the social media era, but social media has amplified the volume of it.”

This is from Lola Sebastian’s excellent video essay we need to talk about Call Me By Your Name, where she dissects the response to what she calls Luca Guadagnino’s “formalist masterpiece.” 2017’s Call Me By Your Name, adapted from the novel of the same name by André Aciman, is a stunning work of art: Sebastian describes the movie as a mirror to the viewer, and attempts to critique the film as a “xerox of a xerox.”

After being a stalwart fan for a few years I was surprised to find that the main conversation around the film online was about the age gap of the romantic pairing — Elio is seventeen to Oliver’s twenty-four. When she announced she’d be covering the film, Sebastian was warned to tread carefully with what one user called “2017’s Lolita.” Even if you have a hard line against the depiction of inequitable relationships in media (fair, but a more difficult line to stick to than you would think), the comparison of a closeted graduate student Oliver to Humbert Humbert is stunningly uncharitable, and suggests an eagerness to decry deviancy rather than sit with discomfort.

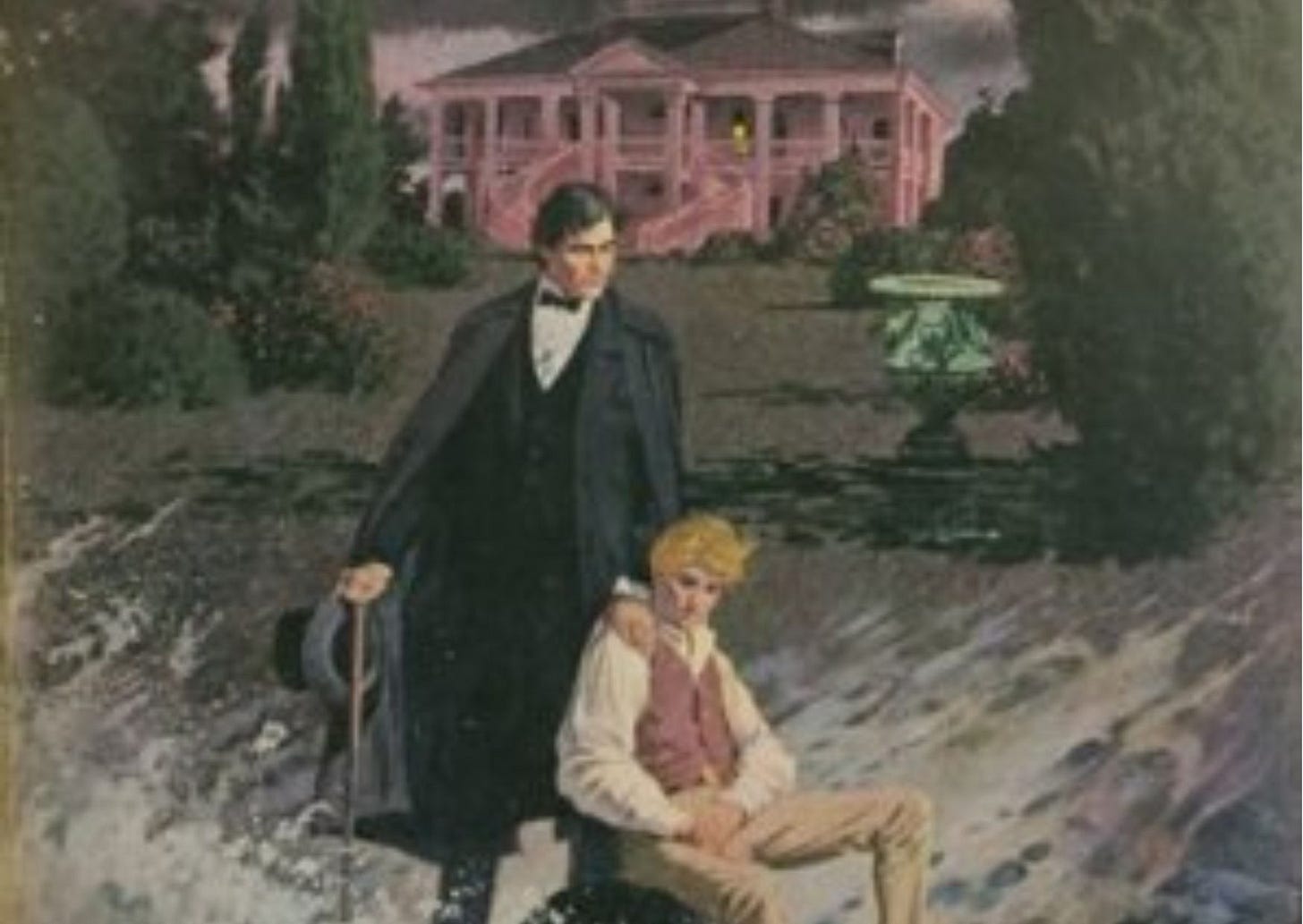

I watched Sebastian’s video essay for the first time while I was reading Vincent Virga’s Gaywyck, a book Avon triumphantly advertised as the “first gay gothic romance” in 1980. It’s also a nasty piece of work. (Complimentary.)

Oh fuck. I thought at the time. How do we get back to this?

Against Interrogation

Something rather stark has occurred in the last twenty years or so: with mass layoffs and publications closing doors, professional media criticism is dwindling, leaving us to look more to social media for conversations on art. The latter isn’t necessarily a bad thing — the reason you’re reading this newsletter at all is because I started a TikTok account for books two years ago — but bite-sized takes on social media are often more compatible with action-based moralism: Do you condone, or do you condemn?

Romance novels in general are underexamined, but the genre is often subject to a less methodological form of ethnography that I’ve been calling in my head “reader interrogation.”1 It’s easiest to pinpoint if you read romance outside of popular contemporary — if you read dark romance or monster romance or historical— some publication, thinking that they’re really doing something, will inevitably ask: Why do you like this? Why do you like this? Why do you like this?

In Vice’s Inside the World of Dark Romance, Where Serial Killer is the New Sexy, Carter Sherman writes that “women who read dark romance told VICE News that they found the blood-soaked, sex-crazed genre to be a cathartic escape from their real lives. Dark romance recognizes that life is difficult and dangerous, especially for women, who face discrimination every day and are more likely to be killed by their intimate partner than by anybody else.” As an isolated observation, this could read as an empowering counter-narrative to the idea that dark romance novels endorse violence and sexual abuse by depicting it, that the power of fantasy is healing and transformative.

But it’s not an isolated observation, and the emphasis on why, be it friendly or antagonistic, preps the respondent for a quasi-moralist approach: you have to justify your taste. You have to be growing or healing or changing. The art is irrelevant, aside from how it’s enriching you.

A consequence of the overemphasis on reader interrogation is that readers view their own taste as either moral or immoral. Do you condone or do you condemn? This has made TikTok a maddening place recently: I don’t care about a stranger’s personal preference2, why is that a relevant response to my critique of a novel?

I mean, I know why. We’re discussing romance novels less and romance readers more. If you have to justify your taste, your preference has to be moral. Because you’re a good person.

Right?

Not beyond that, Robert Whyte? Not to the edge of doom?

In the late 1970s, Vincent Virga was inspired to write Gaywyck after reading a gothic romance that he purchased for his mom. He was surprised to find that the conflict hinged not on a woman in the attic, à la Jane Eyre, but on a neglectful gay husband who would conveniently expire to make way for the true hero, some paragon of masculinity. As a gay man himself, he wondered, “What if genre has no gender?” and after completing the manuscript of Gaywyck he pitched it to Gwen Edelman at Avon. After some convincing, (“Gay men don’t want romance.” Virga recalls her initial reticence in his author’s note. “If they did, there would be books to satisfy the need.”) she showed Gaywyck to Avon’s then Editor-in-Chief Robert Wyatt, who loved it.

It’s difficult to describe Gaywyck in a piece that isn’t solely dedicated to describing Gaywyck3— As Virga notes on his website, the film references alone couldn’t be contained to one scholar’s Master’s thesis— but as a gothic romance there’s a clear pitch: the happily ever after for two gay men in a time where it wasn't commonplace.

Gaywyck begins with Robert Whyte, a seventeen-year-old in the final years of the 19th century. Robbie describes himself by saying “I was menaced by every other human being. I saw everyone’s capacity to inflict pain and expected every intimacy to bring disaster, shattering my inner balance irrevocably. I knew myself capable of such horrors. Terrified of myself, I become terrified of others.”

Robbie is hired as the librarian at the Gaywyck estate in Long Island, helmed by a mysterious proprietor named Donough Gaylord. Donough is older than Robbie — shy, accommodating, and devastatingly handsome.4 Robbie quickly fancies himself in love with his employer, but that love, that juvenile yearning, is complicated by decades of family secrets. The Gaylord family’s dynastic wealth is on par with the Astors or Vanderbilts, but in the devastating early chapters Virga dashes any potential aspirational yearning — the Gaylord family prospered from profiteering off of the Civil War — and they’ve been suffering, perhaps karmically, ever since.

Thirteen years prior to the events of the novel, Donough’s violent twin Cormack met his untimely end, and Robbie is fascinated by what he uncovers about the man. Robbie meets with victims of Cormack’s appetite for destruction, finds his cruel and barbaric trophies, and loses himself in fantasies. “I read books on the subject of twins” Robbie writes in his memoir, “I was possessed by Cormack and Donough Gaylord on my treks up the beach. I imagined perfection as they merged into one flesh. Where my Donough feared to tread, Cormack would rashly charge and carry me away.”

The happily ever after is, of course, for Donough and Robbie. But when genre has no gender, Robbie treads where countless gothic heroines have before: into the hateful forbidden. Cormack — the sadist, the manipulator, the spectre— is the true seducer.

Thirteen Years Thralldom

Two years before Gaywyck was published, Teresa Denys — the pen name of a major Mills and Boon editor Jacqui Bianchi — released the hyper-violent cult-classic gothic romance The Silver Devil, set during the “opulence and intrigue” of Renaissance Italy.

The Silver Devil’s heroine, the poor and illegitimate Felicia, had a single advocate in the world: her mother, whose recent death kicks off the events of the novel. Capitalizing off her isolation, Felicia’s half-brother and his wife begin to abuse her in earnest: giving her the most menial of tasks in the tavern that they own in an attempt to strip her of dignity. She’s not so much sheltered as she is neglected — her brother taunts her with the prospect of being forced into sex work to further instill a distrust for the men of the outside world.

This is not a misplaced fear — Felicia is spotted, then quickly kidnapped by Domenico, the Duke of Cabria, who then takes her as his mistress by force. Domenico has a removed, supercilious cruelty — and Felicia’s fate should he lose interest in her would be catastrophic. The well-being of a woman outside of Domenico's protection is short-lived, and so Felicia has a Scheherazade-type task of keeping him interested piecemeal. She doesn't think she can do it, and she braces herself for the day she fails.

Domenico is not her only villain: Felicia’s proximity to Domenico puts a target on her back at court. One of the metaphorical archers is Piero, Domenico’s childhood friend who pants after her — exalting in a future date where Domenico discards Felicia, leaving her at Piero’s mercy. He gleefully warns her of this inevitability:

"He is a sort of child in that— he wants nothing so much as the thing that is withheld. And once he has it—" he stepped away from me and shrugged elaborately. “He breaks it, like as not, or tosses it undervalued."

"He is a monster," I whispered.

"A royal one.”

Piero is speaking from experience. After he betrays Domenico in a later scene, Piero froths at his former lover, cursing the “thirteen years thralldom” that left Piero angling for affection and proximity to power: “I have never known whether I loved you more than I hated you. God and the devil will have to winnow it out between them. But I fancy the devil will win; God may dislike my making you His rival and tip the scales so that I shall burn. And yet you never loved me, nor anyone.”

Piero’s grasping for Domenico’s attention is laden with a feeling of inevitability, that on the day it finally arrives his lascivious revenge will be devastating. In Gaywyck, Robbie’s directionless fascination with the long-dead Cormack promises a similar upheaval.

“Contemporary and historical philosophers alike have criticized moralism and formalism for their dogmatic polarity, their (arguably) perfunctory one-dimensionality, and their entirely un-accommodating nature in regards to each other.” according to Walker Landgraf in The Challenge of Ethical-Aesthetic Incorporation in Nabokov’s Lolita. In Lolita, “the ethical-aesthetic harmony of the novel allows us to see the obfuscating and one-dimensional nature of both the moralist and formalist schema. In the hands of a formalist, Lolita is an exquisite exercise in layered narrative, wordplay, allusion, and nothing more. In the hands of a moralist, it is an Aesopian parable on the danger and suffering of indulged paedophilia, a piece of “topical trash” which Nabokov himself would spurn, albeit, one with an impressively crafted narrative.”

Like Landgraf and Sebastian, I don’t think the two schools of thought, diametrically opposed, are a particularly satisfying way to view art. But the inanity of viewing The Silver Devil or Gaywyck from a moralist lens, which I can only imagine would end in proselytizing on ethical queer representation, earns it my greater rejection. “God may dislike my making you His rival” is a stunning line that cannot be boiled down to an allegory on the problematic bisexual.

The Prince

“Personally, I don’t think that’s the kind of “relationship” we should be promoting, regardless of whether it’s queer or not. I fail to see how a book with graphic same sex rape scenes is beneficial to the “We Need Diverse Books” campaign. We need positive portrayals of queer characters, yes, but we don't need degrading ones.”

This is a quote from the top-rated Goodreads review of C.S. Pacat’s Captive Prince. Captive Prince started in 2008 as a web serial then, after Pacat self-published to great success, was picked up by Penguin Random House. The fantasy trilogy starts with Damen, heir to the throne of Akielos, betrayed and shipped off to the door of his political enemy, Prince Laurent of Vere. To save himself and plot his eventual escape Damen pretends to be low-born, but Laurent’s studied disdain scorches him all the same.

Captive Prince reminds me quite a bit of the historical bodice rippers that went out of fashion in the 1990s — the politicking in earnest, the violence, the abuse — and the polarized reaction to it has been an interesting glimpse into how bodice rippers would be received by a larger audience. Comparing Laurent, Damen’s initial abuser and eventual love interest, to The Silver Devil’s Domenico seems a bit reductive but… I have indulged in that reductive thought.

In his author’s note for the reissue of Gaywyck, Vincent Virga quotes an Amazon review from 1998 that he found poignant: “It is possible that this book, written before the onset of AIDS, is one of the final glimpses of the optimism that was part of the early gay movement.”

I was a bit dumbstruck when I read this for the first time. Optimism today is frictionless, it is the didactic storytelling that Goodreads reviewer demanded, it is the nebulous idea of “good queer representation” that necessitates reader interrogation. Gaywyck is none of these things: the deep-seated rot of the Gaylord family is not salvaged by a moral love — there’s no tidy bow on the nastiness the book uncovers.

The same could be said of Captive Prince, of The Silver Devil. Perhaps because of decades of public queer trauma and targeted government violence, a loud faction of us have lost interest in viewing ourselves in all our complexities: we must be the harbingers of morality, else we are wasted space.

“We have these right-wing nuts banning queer books while purposefully and casually conflating them with pornography and pedophilia” according to my friend Mel in their (essential!) video essay, they were both the Captive Prince. “And then on the left we keep trying to prove them wrong about us as if they care that they’re wrong. When we attempt to depict ourselves we’re often so paralyzed by our fear of imperfection that we give up before we start, opting instead to tear down each other's work for the sake of content and clout. Or, when we do try, we twist ourselves in knots in an attempt to create the most unobjectionable, morally superior, sexless art that we can in hopes that if we make ourselves as benign and unthreatening as possible then perhaps the people trying to ban our stories from being told will magnanimously come to the conclusion that we do deserve rights, actually.”

Interrogation Redux

I believe that queer media — particularly the complicated, the gross, the contested — has become a lightning rod amongst ourselves due to collective impotence. Powerful people feel so very far away, so what do we do with this anger, this injustice, this hurt? We are within each other’s grasp — we can pile on or uplift. We can condone or condemn.

“From now to the end of consciousness, we are stuck with the task of defending art.” writes Susan Sontag in Against Interpretation. “We can only quarrel with one or another means of defense. Indeed, we have an obligation to overthrow any means of defending and justifying art which becomes particularly obtuse or onerous or insensitive to contemporary needs and practice.”

Knowing that Sontag and Virga were close friends helped close the door on any inkling I had about modifying my pitch of Gaywyck for a modern audience. Gaywyck was not written for homophobic straight people: Virga’s intended readers were gay men like himself, who don’t need to be hand-held to the conclusion that they aren’t deviant. Whatever encompasses “good queer representation,” — an inchoate standard that I suspect Gaywyck would fail to meet, if it were more widely read — is unnecessarily stifling, and detrimental to queer art.

“I knew myself capable of such horrors,” writes Robbie in his memoir. I want us to come to a similar realization. I want us to let ourselves be villains.

[As an aside: Vincent Virga is fascinating. I’d recommend checking out his interviews on Fated Mates and The Last Bohemians.]

They may be an actual term for this, but my attempt at combining the right keywords to discover it was not fruitful.

I want you to imagine me saying personal preference the way that Lydia says feelings in A Gentleman Undone: “‘I’ve never asked you to give the least consideration to my feelings.’ He could picture her holding the word with fingertips at arm’s length, like a scullery maid disposing of a dead rat she’d found in the larder.”

I not-so-humbly suggest you subscribe to the Reformed Rakes podcast, we have an episode on Gaywyck slated for release within the next few months.

Donough turns thirty-one midway through the novel. This is a greater age gap than Call Me By Your Name, although Robbie’s youth is unremarkable after decades of fresh-faced gothic heroines.

This is a great essay, thank you so much. Loved the insights here.

"...don’t need to be hand-held to the conclusion that they aren’t deviant."

Saving this for the next time someone inevitably asks me why I like dark/bodice ripper/monster romance. The unwillingness and honestly the inability to sit with something complexly flawed is representative of the lightning-quick speed we're expected to form opinions now. Social media doesn't allow time or space for holding, dissecting, and clarifying concepts, it demands yes or no opinions on the current hot topic before stampeding to the next "content" that can be raged against. Which is a whole other beast, how works of art are not considered individual pieces of art but instead get morphed into the nebulous cloud of content, a cloud that collapses all nuance in the endless race of consumption.