Shame

The unembarrassed romance reader

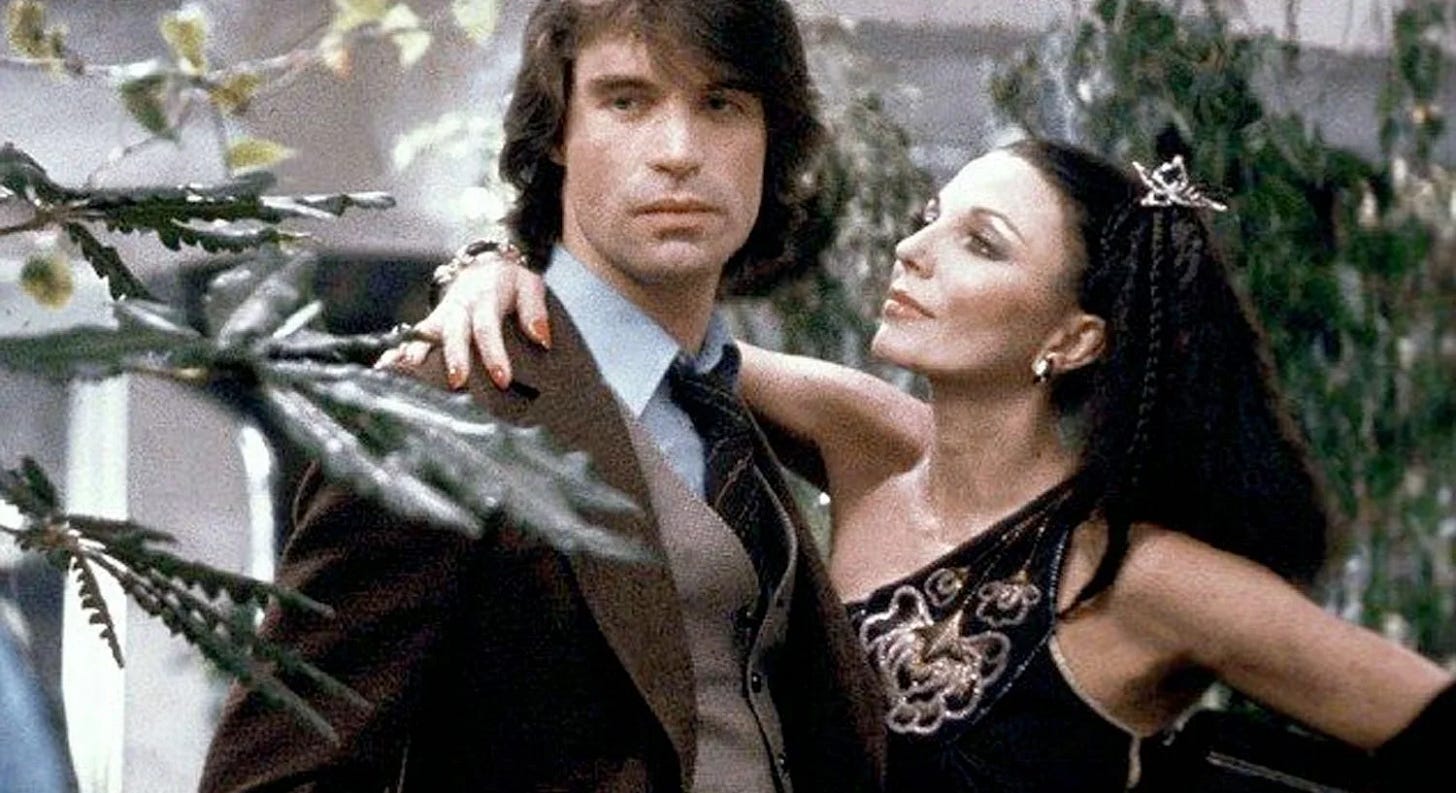

“Don’t you think it has helped perverts?” romance novelist Barbara Cartland grilled Jackie Collins on the set of BBC One’s Wogan in 1987. Cartland, dressed as the gift shop in Portland’s International Rose Garden, rather joyfully played the part of the prudish pearl-clutcher to Collins’ Hollywood maven. Fresh off of reading Collins’ “disgusting” book, The Stud, Cartland saw societal collapse, a degradation of romantic love, and frauds who were instructed to “write like Barbara Cartland with pornography.”

The image of Cartland next to Collins is one in a million: Cartland, decked out as a perennial Christmas ornament, is the bullhorned rebuttal to the pervasive idea that old money whispers. Even Henry Cloud’s fawning Barbara Cartland - Crusader in Pink couldn’t successfully downplay her origins.1 “She finds such connections, like the Dukes and Marquises she writes about, ‘very romantic,” but her own immediate past lies not with the upper aristocracy. Like many writers of her period, she comes from the most fertile of imaginative seed-beds, the dispossessed Edwardian gentry.” Oh heavens, not the dispossessed Edwardian gentry!

Cartland was, famously, obsessed with virginity. When Cloud asked about her heroines, she responded with “Oh, she is always me, and is always virginal of course. She’s something of a Cinderella, and I’ve always thought the point where a young girl falls in love just on the edge of womanhood is the most romantic moment of her life.”

But even with all the shine and the monochromatic pink, Barbara Cartland wasn’t necessarily the most arresting presence on that BBC couch. Collins—garbed in a metallic jacket, eyes thickly lined with smoky makeup, and hair teased to an impressive height—would have fit right in on the set of Dynasty, her sister’s soap opera. Her books, sometimes pejoratively referred to as “potboilers” were simply fun, and The Stud, while perhaps racy when it was first published in the late 1960s, had already lingered in print for almost two decades—more than long enough for the culture to catch up.

“I worry about the people who follow us,” Cartland lectured Collins, “you know people are influenced, and nobody really has worked out what happens when those sort of things go into the brain…. When it’s picked up by the brain it’s like an encyclopedia and you can’t get rid of it.”

I have a suspicion that some romance readers in 2023, learning about Barbara Cartland for the first time, might see their own romance novels as the main source of her ire. They would be wrong.

Stigma

Every time Barbara v Jackie goes viral it elicits a comic joy, which I certainly understand because it’s frankly, incredible that these two women were in the same room. But while Cartland’s morality policing of Collins pulls focus, I’ve always lasered in on an earlier section of the video where she’s addressing the host, Terry Wogan. “We’ve got to go back to the family and save the world. I mean look at the mess it’s in… We’ve got AIDS, we’ve got- everything’s awful, we’ve got children more mistreated than they’ve ever been and I read a lot of history.”

There’s some plausible deniability with what Cartland could be saying here, but any queer person can tell you that “think of the children” plus a reference to AIDs is not going to end in flattering thoughts for the community. My suspicions are correct: in a 1989 issue of Gay Times, Terry Sanderson’s Media Watch column roasts an article in The Sunday Mirror that quotes Cartland worrying that the titles in Gay Men’s Press “could easily pollute children’s minds.” 2

The BBC exchange could be boiled down to closed-door versus smut, and changing opinions on what level of sexual explicitness is acceptable in media, but I’ve never read it that way, particularly because of who these women are. The “political influence” section of Cartland’s Wikipedia page is rather sparse, mentioning her work with the Tories by way of charitable acts, but if you dig through even the most fawning of Cartland biographies you get a less flattering picture: she thought gay people were degenerates, she disliked other women by her own admission (“Women have such petty minds and clutter them up with personal jealousies. Men are so much more direct and honest.”), and she used her discomfort with public sexuality as a cudgel against her competitors.

In The Merchants of Venus: Inside Harlequin and the Empire of Romance, Paul Grescoe recounts a time, late in Cartland’s life, when she’s greeted by the prolific 90s cover model John DeSalvo.

DeSalvo gave Cartland a poster of himself “as bare of chest as he was in person,” and Cartland lectured him, saying “Sex… nasty… love is completely out… What we’ve got to try now is to get rid of all sex, sex, sex…everlasting sex.”

I cannot describe to you how bizarre it is to write about this scene in 2023, when common wisdom is that the covers that John DeSalvo graced are gauche, and where BookTok has to play whack-a-mole with an incessant string of book marketing “experts” who say bare ab covers are tacky and embarrassing. In the words of Rust Cohle, time is a flat circle.3

Thanks to this newsletter I’ve read dozens of romance novel trend pieces and profiles within the span of months, and they are all very, very boring and they all say the same thing. According to every trend piece I’ve ever read, romance was once “denigrated as a guilty pleasure for the desperate, horny housewife,” but now thanks to “Gen Z's openness about loving the romance genre” “we’re moving away from the idea that desires – especially women’s desires – are innately shameful.”

I’m so fucking bored of this weird lie that sales of traditionally published romance novels are any sort of indicator of cultural comfort or openness toward sex, and that the reduced “stigma” around purchasing a book with wide appeal has anything groundbreaking to say about sexual liberation. Even reading this assertion in the most generous terms, there’s something very… heterosexual in this belief. If you’ve spent any time at all on the internet, you know that if you are a little bit of a freak, a lot of these joyous romance readers, absolved of all shame, morph into dispossessed Edwardian gentry.

The Stud

Barbara Cartland was never merely a writer. She was an industry — starting in 1925 she published more than 563 books starting in 1925, in her later years by rapidly dictating to one of her three secretaries. After she died in 2000 the machine cranked on: 160 additional Barbara Cartland books were published posthumously, reaching a whopping 723 printed works. In 1996’s The Merchants of Venus, Paul Grescoe calls her historical romance novels “curiously popular,” for evolved 1990s tastes, while her son Ian, “speaking as if she were General Motors rather than his mum,” asserted that her only competition back in the day was not another author, but all of Mills and Boon.

But Cartland’s books were never called potboilers — that term was reserved for Collins. While it’s largely fallen out of use, “potboiler” referred to a book that was quickly written to cater to popular taste, not to enrich lives but to make money. Quality is subjective, but since Collins’ Hollywood romps were often lumped in with pulp fiction as potboilers, while Cartland’s virginal Cinderellas —rapidly typed with the help of a miniature factory line— neatly avoided the moniker, I think it’s safe to say that sexual content contributes to the label.

Before she started writing, Jackie tried to follow in the footsteps of her very famous sister Joan Collins, acting in British TV and movies until she wrote her debut novel, The World is Full of Married Men, a darkly cutting book about a cheating husband who gets his just deserts. An instant best-seller, Collins followed up shortly with The Stud, a part-salacious, part tongue-in-cheek nightclub drama that revitalized her sister’s career when Joan was cast in the screen adaptation almost a decade later.

While a young Cartland ran in circles with Winston Churchill and Lord Mountbatten, a teenage Collins orbited a different kind of wealth and influence, trailing her sister to attend house parties with Marlon Brando. Decades later, after her successful writing career captured the attention of everyone who wrote her off as a pale imitation of Joan, she moved her family to California and began her Hollywood series.

Alexandra Heminsley in The Sunday Times recounts a conversation with Jackie’s daughter Rory in the documentary Lady Boss, where Rory asserts that her mother’s “much-pilloried leopard-print look” was her version of drag, a costume that signaled she was at work. It’s fun, it’s camp, and it’s why it’s a bit difficult to wrap my brain around the aesthetics of Barbara Cartland, whose flashy pink wardrobe (which was astonishingly cheap!) was not a far cry from the theatrical femininity of queer icons like Tammy Faye Baker and Jackie Collins. But while Cartland was dwelling on the so-called perverts, Collins embraced them, eventually as a guest judge on RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 2. (This was before Drag Race was the multi-continental behemoth we know it as now— when it was still cordoned off to the queer cable TV channel Logo, and the queens wore Wet Seal rather than Bob Mackie.)

I can see why romance readers might view the BBC exchange as “modern attitudes about sex versus the old guard,” and align themselves with the former, since we are now free of shame and embracing sex. (Can someone write an article about this please!) But Collins’ connection to drag and queerness, and Cartland’s homophobia, helped me connect the dots a bit better. Hey queer people: when they say “reducing stigma” about sex, they aren’t talking to us.

I’m a big fan of Jayne Ann Krentz, but I always think of her opening line in the 1992 romance anthology Dangerous Men and Adventurous Women with a sort of amused disbelief: “Few people realize how much courage it takes for a woman to open a romance novel on an airplane.”

The unhidden romance novel signals to outsiders something akin to, “Hey, this person is potentially reading about sex!” which then leads to embarrassment, which is something that we have apparently made great strides fighting since the early 1990s. I see where this is coming from— while I’m no fan of the common saying that romance is “for women, by women,” it would be folly for me to pretend that women aren’t, largely, the perceived romance reader. It’s tough to grow up in a world where your hobbies are gendered and labeled frivolous, and your sexual appeal is inversely proportional to your ability to publicly express it on your own terms.

I’m deeply empathetic to this dilemma, but I get quite frustrated with how heterosexual and cisgender this conversation remains— the already exclusionary “for women, by women” saying has an invisible asterisk that denotes which women we are talking about. Even now, queer people are playing an entirely different game when it comes to open sexuality— one with moving goalposts. Conservatives view visible queerness as inherently sexual, which is why even the most sanitized, PG queer media is contested as deviant.

What happens then, when you’re a little bit of a freak?

The Ick

Last week a teenager tweeted “bring back vanilla sex in books” to joke about four screenshots from TikTok chronicling a sex scene where a man inserted a tampon into his love interest while she slept, then removed it with his teeth. I don’t think it’s particularly noteworthy that a teenager feels this way about this very specific kink, but the gleeful quote tweets and commentary from adults acting like this (kind of benign?) scene is mind-numbingly stupid and gross is a pretty clear NO FREAKS banner to the casual observer.

My TikTok enemy that created the viral Book Jail series does the same thing for clout. After soliciting submissions for literary incarceration by form, she’ll type out a scene from a book of context. “She’s obsessed with her cult leader brother that has flippers for limbs, his followers cut off their limbs to be like him and she makes her 11 year old brother telekinetically transfer their brother’s sperm inside her uterus to impregnate her” is how she describes Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love, the National Book Award finalist that’s just as moving as it is unsettling. Dunn wrote a book about finding beauty in ostracism, but as one commenter put it, “each author on this list needs therapy and/or jail.”

The politics of discomfort, while not always obviously targeted at queer people, typically manages to catch us in the crossfire. Well-meaning romance readers tout the genre as didactic, instructing young men and women about consent and communication, but I would like to take a blowtorch to this idea for a litany of reasons. Barbara Cartland thought that women should be virgins until marriage, so her heroines were virgins until marriage. Barbara Cartland also thought that exposure to gay men would pollute children’s minds, so she was in favor of banning the Gay Men’s Press. (Does this remind you of anything?)

The romance trend pieces that say we’ve evolved past shame into a new enlightenment always tout the usual suspects: best-sellers of heterosexual romance like Emily Henry, Beth O’Leary, and Ali Hazelwood. I don’t think it’s a knock on their work to say that what they write is largely inoffensive, so that’s why some readers can simultaneously be liberated by their sex scenes while turning into Barbara Cartland 2.0 once a different work gives them the ick.

The Perverts

I’ve been writing about romance and talking about it on TikTok long enough to have weathered more than my fair share of lectures from strangers about morality. I’m also a John Waters fan, so I have developed a strange coping mechanism. When someone calls me disgusting or tells me to get help I ask myself: is this something they would also say to John Waters? (The answer is always yes.)

If you’re not familiar, John Waters is a writer and director nicknamed “The King of Filth.” He might be best known for directing 1988’s Hairspray with Ricki Lake, but he’s likely more infamously known for 1972’s Pink Flamingos, where his longtime collaborator, the drag queen Divine, ate dogshit on camera.

I think romance readers could learn a thing or two from John Waters about morality, though. To say that Waters was uninterested in didactic storytelling is an understatement: he mostly wanted to shock and make you laugh. He was also heavily influenced by pornography, and included porn stars, notably his close friend and muse Traci Lords, in his more mainstream films like Crybaby and Serial Mom.

Decades later, quite a few romance readers and authors are still quick to disassociate the genre from pornography, which is not only a losing battle in a world where Nora Roberts counts as porn, but is an act of cowardice. True, not all romance novels depict sex, but what is a more impactful focus: splitting hairs about the definition of “pornography” even though conservatives don’t care and are operating in bad faith, or aligning with sex workers to fight the right-wing backlash we are currently in the midst of?

Shame is, a lot of the time, extremely personal. The feeling can be triggered by your upbringing, your religion, your prejudices, or something upsetting that happened to you in the past. Overcoming shame is, obviously, a different journey for everyone, so it’s another conveniently untrackable barometer for progress.

While their work seems like it’s worlds apart, Jackie Collins had a proximity to queerness that, aided by the (then) taboo storylines in her novels, elicited the same panic from critics as John Waters’ filmography. “Don’t you think it has helped perverts?”

Why, yes I suppose so.

:)

According to the authorized biography by Gwen Robyns titled Barbara Cartland, Cartland is “a direct descendant of the oldest Saxon family in existence.”

Gay Times was not cowed by Cartland, stating “It’s hard to imagine that the works of any of these philistines and would-be book burners adds much to the quality of human life. Given the garbage that Cartland churns out and the universally mocked writings of Archer, I would think that GMP are quite happy to be in a different league. And forward to the High Street!”

I don’t know what this means.

"Decades later, quite a few romance readers and authors are still quick to disassociate the genre from pornography, which is not only a losing battle in a world where Nora Roberts counts as porn, but is an act of cowardice. True, not all romance novels depict sex, but what is a more impactful focus: splitting hairs about the definition of “pornography” even though conservatives don’t care and are operating in bad faith, or aligning with sex workers to fight the right-wing backlash we are currently in the midst of? "

Oh yes. Latest case in point--the Spoutible Romancelandia kerfuffle. I saw that one blow up in real time, but to me what was most telling was that the same pale-shaded ladies who just loooved the site because it was "safe" and "comfortable" also associated romance writing and romance writers with porn. Said ladies had no problems with leaping onto Twitter and pulling one of the most toxic of pile ons (which made me wonder just exactly would happen over on Spoutible if they decided to turn on one of their own). It was enough for me to write off that platform because while I write reasonably tame science fiction romance, the Cartland-esque sneers that I should go promote my work on a porn site told me all I needed to know about the tone of *that* platform.

Then again, I almost think that *those* ladies would find Cartland...problematic.

As for Jackie Collins? My late father-in-law faithfully read every single one of her books. I borrowed his books. He was from the Greatest Generation, World War II vet who fought in the Philippines. She was hardly the only potboiler writer of that era, but I'd say that she was one of the better ones.