This essay is built from research I did for the Reformed Rakes podcast. You can listen to Janet Dailey: Part One, and Janet Dailey: Part Two now, wherever you get your podcasts.

What do you think of when I say the name “Janet Dailey?” If you weren’t a romance reader in the 1970s through the 1990s, maybe the name means nothing to you at all. Maybe you’ve noticed how much shelf space she takes up in used bookstores. Maybe you’ve heard her name as a pejorative, but don’t quite remember why. Or maybe, like a lot of romance readers, you remember that she confessed to plagiarizing from Nora Roberts in 1997, a shocking development that tanked the reputation of one of the genre’s most successful writers.

Until last August, I was largely in the first category. I had just wrapped up recording an episode of Reformed Rakes on romance’s ostentatious grande dame, Barbara Cartland. Part of our episode on Cartland covered the plagiarism accusation that Georgette Heyer privately lobbed her way in the 1960s as covered in Jennifer Kloester’s Georgette Heyer: Biography of a Bestseller. Heyer’s accusations were hilariously petty and somewhat specious, so I wanted to compare Cartland to a scenario that was clear-cut, and no situation seemed more obvious than Janet Dailey’s. I didn’t realize how much this decision would impact the next ten months of my life.

A cursory search of “Janet Dailey” and “plagiarism” will take you to a few recent blog posts obliquely recapping the scandal, but the more I eked my way back to 1997 and earlier, the more I noticed another name cropping up over and over again: Bill Dailey. Janet’s husband.

The story got a lot more complicated, and a hell of a lot weirder. I couldn’t think of anything else. I still can’t.

Janet Haradon was born in the miniscule town of Storm Lake, Iowa, in 1944. Janet’s father died when she was only five years old, and her mother, who worked in a mercantile store, re-married seven years later. This union moved Janet to the “big city” of Independence (at the time, population of approximately 5,000) where she flourished as a social butterfly. She was also thwarted early by her own ambition, telling interviewer Sonja Massie in The Janet Dailey Companion that she wanted to write but had no interest in reporting. Her teachers couldn’t delineate a path where she could become a successful novelist, so she tossed the idea of college aside entirely. She was voted “Most Likely to Get Married and Have Five Kids” by her classmates.

After graduating, Janet moved to Omaha to start secretarial school, but she didn’t stay there for long. One day Janet was walking back to her dormitory with her roommates who had just gotten out of mass, only to find Bill Dailey smoking outside the building. “Looks like you’ve been to church” said Bill. “Did you say a prayer for me?”

“Yes,” Janet responded. “You look like you need one.”

It wasn’t long before they married.

Janet was a bride by her early twenties, but Bill Dailey, fifteen years her senior, had already lived several lives by the time they met. Bill was born in New Orleans to parents deeply entrenched in the hectic, transitory showbiz lifestyle. For a time, Bill’s father owned a club on Bourbon Street with Tex Ritter (of High Noon fame), but they didn’t stay in Louisiana — they traveled in carnivals, circuses, and even worked at the Grand Ole Opry. As a young teenager Bill joined the Merchant Marines, moved to the Phillipines, and then returned to the carnival during a restless period, referring to himself as “dimwit and dumbnothing.”

Tired of constant travel, he settled in Omaha and started a commercial painting business. That restlessness never left him; Once the painting business became successful he kept adding to his entrepreneurial repertoire: owning a construction company and eventually moving into oil speculation. He was on his third marriage and had five kids by the time he met Janet, but only had a relationship with his two youngest from his latest marriage.

After meeting Janet and learning she was in secretarial school, he convinced her to drop out and get on-the-job training at his construction company. Janet, who wasn’t too keen on school anyway, did precisely that.

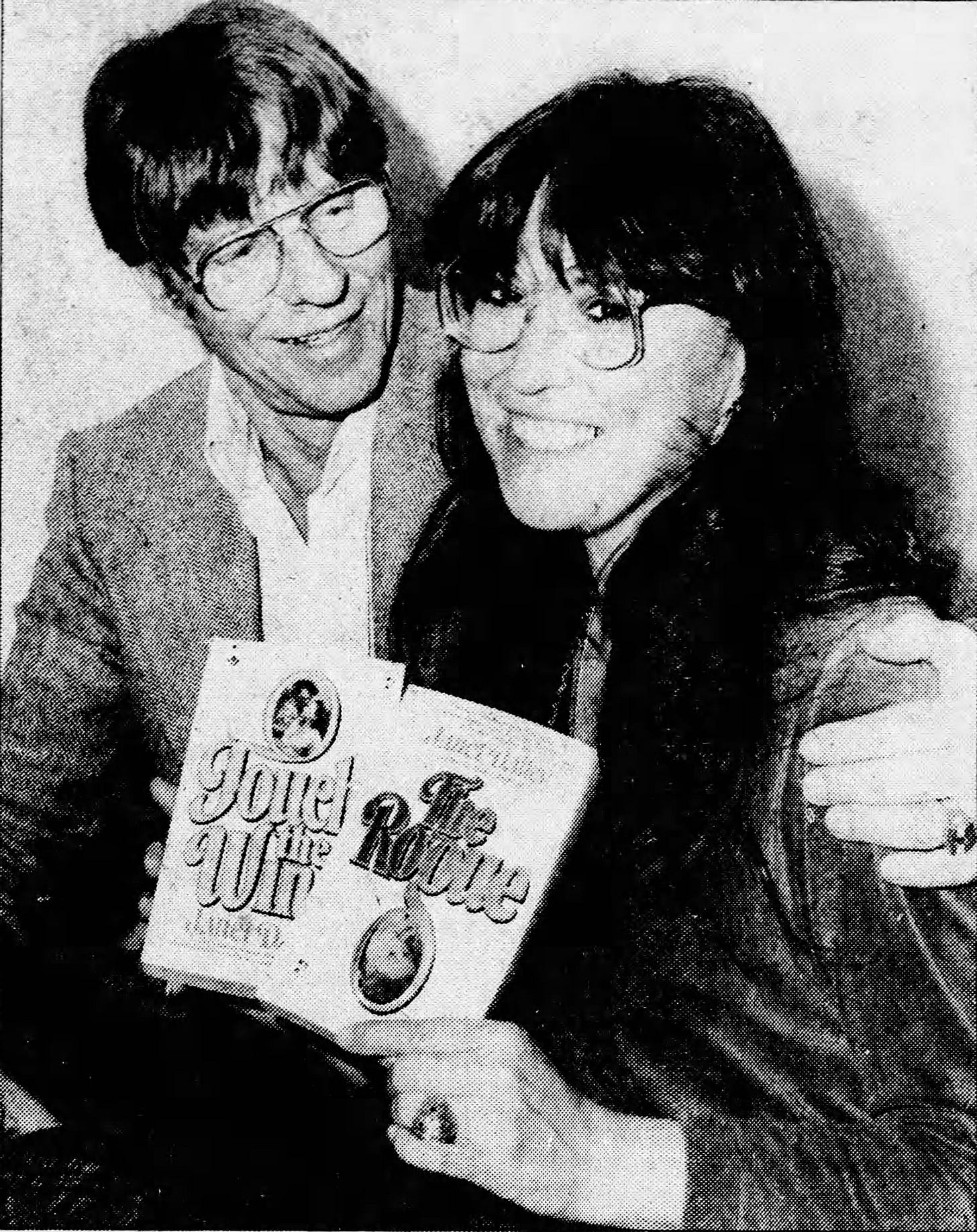

“Bill was no romance-novel hunk,” wrote Paul Grescoe in The Merchants of Venus: Inside Harlequin and the Empire of Romance. “Well below six feet, weighing in at about 130, with glasses and a well-lined face. He had been a carnival barker and fire-eater and still had hearts and snakes inscribed on his arms from his time as a circus tattoo artist.”

“But is he a tall, handsome, blatantly virile sun god?” Frank Rasky mused in the Toronto Star. “Hardly… he looks like a bespectacled, sandy-haired wimp. And far from being arrogant, bearing the hint of a “caged anger” characteristic of his wife’s fictional heroes, he is endowed with a very garrulous gift of gab – a trait you’d expect from a former carny barker, fire eater, sword swallower, and tattoo artist.”

The Bill the world saw and the Bill that Janet saw did not neatly align. She told the Scotts-Bluff Star Herald that Bill had romance novel hero traits: “Dominating. Adventurous. A lover of wide-open spaces. Possessive. A borderline chauvinist who expects a woman to be essentially feminine while capable of dealing with any and all aspects of the business world. A romantic beneath a hard exterior. A keen sense of humor. A lightning-quick temper. Too rugged to be handsome in the accepted sense of the word.”

Janet told Massie in The Janet Dailey Companion that after she and Bill worked together for thirteen years in Omaha, they decided to sell the businesses and adapt a more transient lifestyle in their Airstream trailer. After years of doing this, the thrill of seeing the country wore a bit thin, and during this period of her life Janet started reading Harlequin romances. She would often comment to Bill that she thought she could write a better romance novel, and Bill responded with the equivalent of put up or shut up. Approximately six months later Janet’s first novel, No Quarter Asked, was born.

According to Steve Ammidown, No Quarter Asked was initially published by Mills & Boon in 1974, and reprinted by Harlequin in 1976. Harlequin purchased Mills & Boon in 1971, but when Dailey pitched her book to the Canadian behemoth, she was told they were still reprinting UK-based Mills & Boon romances for a North American audience. Dailey was Mills & Boon’s first American author, but possibly because Harlequin is the bigger name in America, Dailey’s legacy is more neatly tied to early Harlequins. Regardless, No Quarter Asked was a success, and soon after Bill was fuelling Janet’s ambition.

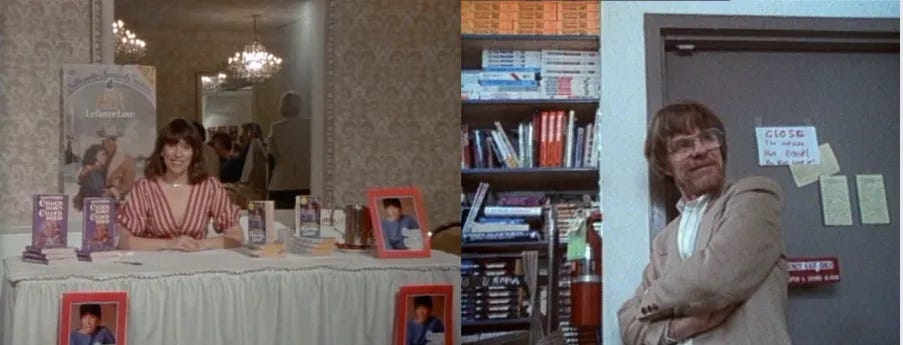

“After Jan wrote her third book, basically I asked Janet one day ‘Do you wanna become the number one author in the world?’” Bill told George Csicsery in the documentary Where the Heart Roams. “And she said yes, if that’s what I wanted. So I started laying out plans, and of course one of those plans was that we’d travel ‘round the country, and we’d do a book in each state for the Guinness Book of Records.”

This became Janet’s Americana series, fifty books in each state. Janet had worked for Bill for over a decade, so this was a drastic shift: now Bill was in a supporting role, handling the research for Janet’s books, the contracts, and the publicity. Janet’s tasks were no less laborious: she had to write.

It’s hard to wrap my brain around how big Janet Dailey was by the early 80s. Readers were voracious, romance was booming, and there weren’t enough authors writing in the genre to keep up with the demand. Everyone wanted more, more, more, and Dailey, with her rapid writing pace, provided. By 1985 she had sold well over 100 million books — in 2024 the media is frothing at the mouth at Colleen Hoover’s sales, but Hoover isn’t touching Dailey from four decades ago.

Janet Dailey didn’t get married and have five kids. She got married and built an empire with her husband, but not everyone saw it as egalitarian.

In a Chicago Tribune article about the documentary Where the Heart Roams, Donald Liebenson referred to Bill Dailey as Janet’s “Svengali husband.” This was a common media invocation: “Born in New Orleans, Bill Dailey grew up in carnivals and circuses, and was married three times before he met Janet, who came to work for him as a secretary when she was 18,” wrote Evelyn Renold in a 1980 New York Daily News article. “Without embarrassment, Bill will tell you he “only went to the fifth grade”; questioned about the “Svengali" label, he asks what the word means. But few doubt his shrewdness, or his skill in promoting his No. 1 commodity: wife Janet.”

When “carnival barker” — a strangely old-fashioned pejorative — fell short, journalists would clarify their disdain for Bill: “When talk turns to the latest product, Bill refers to it as “the book we’re writing” wrote the Columbia Daily Tribune. Later, a subtle dig: “With a fifth-grade education, he edits her output day by day.”

Bill was a wiry man with a thick Southern accent, and according to the Springfield News-Leader, he was also “blunt and known for his salty language.” Janet frequently and emphatically cited Bill’s support as the reason for her success, but his demeanour raised hackles. In a 1987 interview on the show Good Morning! Eileen Prose asked, “And it was your husband Bill who told you to write that book?”

“Well, he didn’t put it quite that way,” Janet responded. “He said get up off your rear, write that book, or shut up, because I’m tired of hearing you talk about it… I was like thousands of - thousands of authors. Always wanting to write a book, someday.”

This was a frequent interview anecdote for Dailey — I’ve read at least eight different iterations of it. Janet, who described herself as an ambitious person paralyzed by the idea of failure, likely thought she was telling a story about a challenge, a forceful push in the right direction. Everyone else just heard “Shut up.”

Referring to Janet as Bill’s “No. 1 commodity” was a paternalistic way to speak about one of the most successful authors of the decade, a winking faux-concern that plagued the Daileys for most of Janet’s career. If Janet had never spoken of her working relationship with Bill, or addressed these concerns at length, maybe their sincerity would be more plausible.

“I’ve had more than one person over the course of my career— people usually involved in business— who believe that I’m totally dominated by him. Occasionally they’ll tell me “Well, can’t you think for yourself?” or “Can’t you make a decision for yourself?” But what they fail to understand is that it’s this “working thing,” Janet explained in The Janet Dailey Companion.

“My husband has done all my research for the books, so that I as the writer am not going out there and physically getting the research,” she told Bob Cromey in a 1985 About Books & Writers radio interview. “So basically all I have to do is come up with the idea and write the book. He comes up with the contract negotiations, all the publicity arrangements. I never get involved in all that side. It’s very much a team effort. A lot of people don’t recognize that Janet Dailey’s name appears on the book but if it wasn’t for Bill Dailey working and totally handling the other side of the business career… it’s 50/50.”

Bill told Massie in the Janet Dailey Companion that he couldn’t sit still, that once a project is complete he can’t sit with success, but he has to move on to the next venture. Local papers bear this out — the businesses endeavors in Omaha, getting national attention on Janet’s career through cross-country promotion, and then finally Branson.

In 1979 the Daileys tired of travel and settled in Branson, Missouri, which is sometimes billed as the “Vegas of the Ozarks.” That’s… true if you squint.

Branson is a stop through the windy roads traversing the beautiful Ozark mountains. It’s a vacation destination and country music hub, filled to the brim with theaters and live performers that court a decidedly family-friendly audience. “What happens in Vegas,” could mean literally anything. “What happens in Branson” is likely a theater packed with southern octogenarians, safe in the knowledge that they’re in for a show without cussing or nudity.

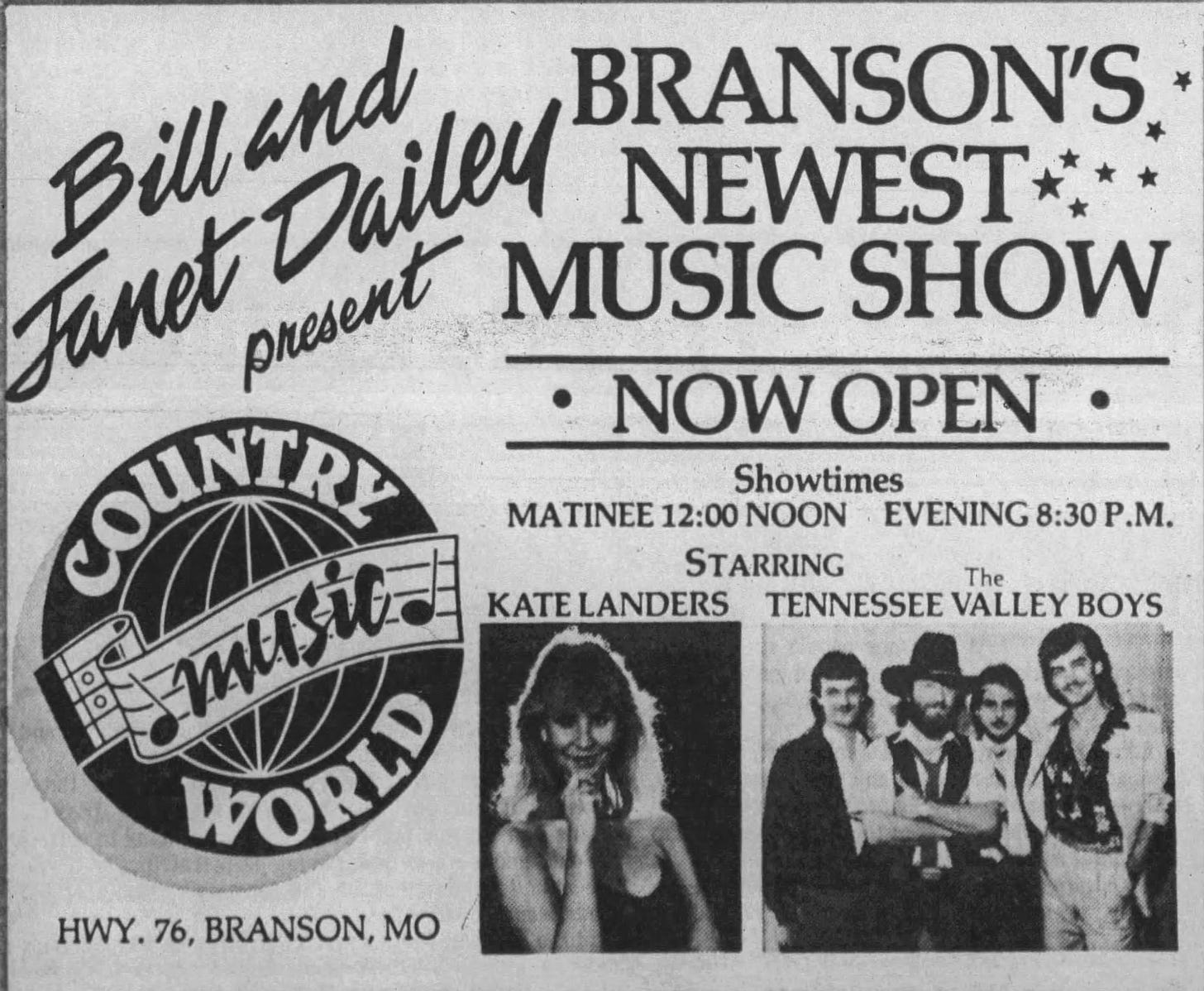

Bill Dailey, a profane chainsmoker, was not the type of person you’d think would help put the city on the map, but when the Daileys hired a group called The Tennessee Valley Boys to perform for one of their parties, Bill saw an opportunity. He and Janet formed Janbill Productions, and managed The Tennessee Valley Boys (who later changed their name to Branson!, a decision that annoys me to an unreasonable degree), along with a singer named Kate Landers.

In the 80s Branson had a small fraction of the theaters it’s currently known for, and one of them was Hee Haw, a venue specifically built for the stars of the hit country music variety show. When the Hee Haw Theater shuttered, Bill bought it and converted it into Country Music World, where The Tennessee Valley Boys, Kate Landers, and local legend Shoji Tabuchi would perform.

The Daileys were local celebrities in Branson in the 1980s with constant plans for expansion: hotels, nightclubs, and more theatrical venues. Bill’s managerial prowess, which is now only spoken in conjunction with Janet’s writing career, was garnering notice with romance authors and Branson residents alike. In the documentary Where the Heart Roams, author Melodie Adams said she flew to Branson to speak with Bill, and later dedicated her first Silhouette novel, I’ll Fly the Flags, to him in thanks for his guidance.

In the 90s Bill managed a Branson singer named Jennifer Wilson, who had a show called “Jennifer in the Morning” at the Dailey-owned Americana Theater. A Springfield News-Leader article called “Singer’s popularity rises with some ‘Dailey’ help” outlined Bill’s role in guaranteeing Wilson’s success, implying that something sinister was at play: “Dailey keeps a tight rein on her plans– she won’t even tell her age without his permission.” This is the type of detail about managers that is often kept under wraps, but Bill’s controversial local celebrity always seemed to push him to the forefront.

In the late 1980s, after singer Kate Landers divorced her husband, her ex appealed the child custody ruling, citing Kate’s dreams of fame, spurred on by Bill, as a reason she was unfit to be a mother. Bill and Janet, as well as Janbill, were both named in the document, which accused Bill of some very un-Bransonlike behavior. “Bill Dailey has had a varied career, including being a pitch man for "freak" and "hoot" shows in carnivals, a stint in the Merchant Marines, and various business enterprises, including the management of Janet's career,” according to the document. “He uses obscene language, such as the words "fuck," "teats," and "ass" as a part of his ordinary conversation and, at the present time, spends a good part of his time in the promotion and management of young females who are seeking fame as writers and entertainers.” The appeal was denied, but Kate Landers also disappeared from the Branson papers around this time, presumably retiring from the stage. Bill would go on to manage Jennifer Wilson instead.

Bill’s most notorious act occurred in 1985, when he shot a man named Steve Goodwin outside the Wildwood Flower, a supper club that the Dailey’s owned. According to Goodwin’s initial statement, he spent two hours at the Wildwood Flower and then left. He later returned with his employer, a man named Mike Summers, so that Summers could make a phone call and Goodwin could use the restroom. He saw Bill Dailey and some companions standing outside the front door of the venue, and was surprised to see that Bill was holding a gun. Goodwin asked Bill why he was aiming a gun at him, and Bill responded that he was a deputy sheriff. “I was about to say that didn’t give him the right to pull a gun on me when he shot me,” Goodwin said.

Bill was charged with felonious assault, and his lawyers argued that he was acting in self-defense, citing Goodwin’s prior criminal record. In 1986 the charges ended up being dropped after Goodwin changed his initial statement: “I recall lunging for the gun, attacking and threatening as Mr. Dailey backed up, ordered me to stop, to keep back and with my size, my condition, my conduct, Mr. Dailey would have been almost stupid to let me get my hands on his weapon. He had no choice but to defend himself as I am beginning to remember the events.” He later added, “we must have seemed to be the head of the Hell’s Angels in Taney County.”

Goodwin’s former lawyer, irate that he was cut out of his expected payout from a $1 million civil case against Dailey that Goodwin also ended up dropping, accused Bill of paying off witnesses. Dailey’s lawyer Stephen Rea is quoted in the Springfield News-Leader predicting this accusation’s longevity: “There will be those in the community who will always say – no matter what result might occur – that it is Bill Dailey’s prominent celebrity and money that got him off. It is most unlikely that substantial numbers of people will ever believe that he got off because justice under the law required it.”

Bill Dailey’s last prominent legal battle of the 80s was around the 1982 movie adaptation of Janet’s novel, Foxfire Light. The movie, set in the Ozarks and starring Faye Grant (stunning) and Barry Van Dyke (adequate), also featured heavy hitters Leslie Nielson and Tippi Hedren in supporting roles. Janet wrote the screenplay and Bill executive produced the film, initially approaching a Kansas City man named Laurence Winters to direct as he wanted to use local talent. Bill changed his mind, instead choosing to “go Hollywood,” and Winters sued for breach of contract and fraud. In 1988, a judge ordered Dailey to pay Winters the hefty sum $805,000.

The Daileys did not seem to be hurting for money. According to the St. Louis Dispatch, Janet was so bankable that Little, Brown and Company, which was at the time a more prestigious hardcover house, offered her a $10 million contract for five books in 1988. ( “She was looking to upgrade her image and they were looking to downgrade theirs,” an anonymous publishing source told the New York Daily News.)

In 1992, Bill built a mansion for Janet called Belle Rive, which sat alongside Branson’s Lake Taneycomo and would later be featured on an episode of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. That same year, Bill and a business partner bought Cash Country Theater,— the abandoned venue built for a Johnny Cash residency that never materialized— for 4.1 million dollars at auction.

Despite this success, the early 90s were a tough time for the Daileys. The Associated Press reported in 1994 that “Dailey’s frenetic writing pace has slowed down to about one book a year now. She didn’t publish a book in 1993 because of personal tragedies – two of her stepbrothers died of cancer, and her husband underwent successful cancer surgery.” Bill Dailey, a lifelong chainsmoker, had been diagnosed with lung cancer, an event that undoubtedly threw a wrench in their deeply entwined personal and professional lives.

His cancer treatment was successful, and it seemed like things were on the upswing: Janet signed a four million dollar contract at HarperCollins, apparently still so bankable, according to The Merchants of Venus, that she wasn’t asked to write “a single word of outline.”

You know what’s coming, right?

The Janet Dailey Companion is a very strangely formatted biography. Its starts in an almost yearbook layout —highlights, astrological sign, hobbies— then moves to the seemingly unedited interview portion with Sonja Massie. At the end, every single one of Janet’s books are listed out in order, with publishing date (ignoring the Mills & Boon years), title, and summary. The last book entry in The Janet Dailey Companion is bitterly poetic: a 1996 release called Notorious.

Nora Roberts likely does not need an introduction here, but for the uninitiated: her career, which started in 1981 with the publication of a Silhouette novel called Irish Thoroughbred, is the stuff of legend. Her writing output is prolific and varied — she published 66 novels in the 80s alone. The current figure is above 220, and includes her insanely popular In Death series, which she publishes under the pen name J.D. Robb.

Roberts’ 1988 romantic thriller, Sweet Revenge, was republished in 1997, the same year that Notorious was printed in paperback. A reader who read both books back-to-back noticed similarities and alerted Roberts to potential copying. Shocked, Roberts purchased Notorious from a bookstore and independently confirmed what the reader suspected: Janet Dailey, a writer she had known for years, had plagiarized her work.

Notorious was not the only book that was called into question: 1991’s Aspen Gold, 1992’s Tangled Vines, and a 1997 release called Scrooge Wore Spurs are all Dailey books that have plagiarized passages. While those are the four Dailey books that have been publicly identified, the copying is not one-to-one. According to a 1998 Publishers’ Weekly article, Roberts’ copyright suit against Dailey estimated that the author lifted from at least 13 of her novels, and a substantial amount of copied work went into in Aspen Gold, specifically.

Roberts wrote on her blog and spoke to the Fated Mates podcast about this stressful time, saying that Dailey’s team pressured her to keep quiet about the copying and work to settle it internally. Because of this, she was blindsided by an ill-timed about-face: Dailey confessed to her plagiarism in a press release right before the 1997 Romance Writers of America convention. Roberts, who was slated to receive a Lifetime Achievement Award, now had to deal with the reactions of the romance community head-on. Dailey, who was also set to attend to hand out the Janet Dailey Award —given to an author that writes about a social cause or issue— backed out of the event entirely.

Public memory of this event is fragmented, with the exception of the media reaction, which really stuck out in romance readers’ minds as unnecessary cruelty. Everything was a bit of a joke, and romance novels were the punchline.

The Associated Press started their coverage with, “There is a reason romance novels all seem to read alike.” The Washington Post got creative: “Heaving bosoms and throbbing loins are all very well, but if you really want to make a romance writer breathe heavily, try pinching her prose.” Newsweek’s article “The Queen of Hearts Gives Up Her Throne” mused, “Plagiarism? How can you tell when all this stuff sounds the same anyway?”

In her press release (which you can read in full here), Dailey cited psychological stress brought on by personal tragedies, which included the death of her brothers and Bill’s cancer treatment. This was not interesting enough for Newsweek, who brought Bill back into the discussion in a big way.

“In fact, the illnesses may have been only part of her problem,” wrote Marc Peyser. “Dailey began writing in the mid-'70s at the urging of her husband, Bill, whom she met while he was the married owner of a Nebraska construction company where she worked as a secretary. Bill, 15 years Dailey's senior, exerted extraordinary control over his wife. He managed her business affairs and did all her research - including taking the notes when they piled into their trailer for trips to locales for the next novel. ‘He called the shots,’ says Bambe Levine, Dailey's press agent until 1989, ‘and she listened.’”

Peyser then called Bill “a former carnival barker, [who] has been a notorious character on the romance-novel landscape.” (“Did ‘carnival barker’ used to mean something more obviously morally repugnant?” my podcast cohost Emma asked when we spoke about this.) The reasonings Newsweek provided for Bill’s notoriety are the 1985 Wildwood Flower shooting, and the 1988 order to pay Laurence Winters $805,000 over Foxfire Light, drawing a direct connection to these events and Janet’s supposed financial woes (it’s unclear how these events fully negate Janet’s multi-million dollar contracts) in the 1990s.

“Every dime Janet made had to go to paying off all these legal fees and debts from his entrepreneurial ventures,” Bambe Levine told Newsweek. “If someone put a gun to your head and said you have to write a best seller in six weeks, are you going to be able to produce?”

The metaphorical use of gun to your head is doing quite a bit of work to recontextualize a working relationship that Janet Dailey had nothing but praise for. It’s a continuation of this faux-concern that Janet could’t seem to shake — the reasons Janet plagiarized are immaterial to the harm she caused, but if you truly wanted to know, why discard her concern over her husband’s health?

The August 1997 Newsweek article may have started the trend of honing-in on Bill, but others were happy to follow suit. “Janet Dailey’s problem is that she loves and is married to a man who may be the prime case (most of her friends feel) of her present mental condition, as well as this very serious legal situation,” Dorthy from Rochester, IL wrote to The Romantic Times in their November 1997 issue. “Yes, he has invested Janet’s money there, helping the local economy, but he has also been a real nincompoop. He has a temper as big as his ego, and has been involved in several serious altercations, and actually charged with a shooting. Guess whose love, whose money bailed him out?”

In December of 1997, the Romantic Times released their major coverage of the scandal called The Summer of Discontent: The Rise and Fall of a Romance Icon, written by Anne Sullivan. The article is laden with factual inaccuracies: referring to Foxfire Light as “Firefly Light,” saying Janet’s book The Great Alone was published by Simon & Schuster’s Pocket Books, when it was with Poseidon Press, and extensive pondering about formerly successful authors like Irving Wallace, who had “disappeared” from The New York Times best-seller list in 1997. Irving Wallace died in 1990.

The piece follows Newsweek’s line of thinking and ups the ante, saying that Dailey was “raised fatherless” (Dailey was raised by her stepfather, a man named Glenn Rutherford), a detail that is used to imply unique susceptibility to an older man like Bill, “who divorced the mother of his children to marry her.” That detail is also misleading: according to Janet, Bill and his ex-wife Judy were already separated when they met, and the former couple remained friends. Judy would visit the Daileys at Belle Rive in the 90s.

There are paragraphs of contrasting details about Nora Roberts’ master carpenter husband and Bill (they hilariously include the detail that Roberts’ husband Bruce is “tall”), but the sticking point is that Roberts’ husband wisely stays out of her business, something that Bill decidedly did not do, to Janet’s supposed detriment.

“To this day, many writers often make two vital mistakes. First, they increase their overhead as if there is no tomorrow, and second, more than one husband has quit his job to dabble in sophisticated investments and ventures that fail,” wrote Sullivan. “Many remember the late Sylvie Sommerfield’s multi-contracts, her plagiarism scandal, plus the health and financial problems brought on by the failure of investments. She ended her life tragically. On the day of her funeral, process servers arrived at her doorstep.

It has been shown that many romance writers aren’t business-like. Some say writing utilizes the right hemisphere of the brain and business logic uses the left. Thankfully, most writers rely on their agents and/or a literally lawyer to take care of the business side of their career.”

This part about Sommerfield was so needlessly cruel that I had to take a breather after reading it for the first time. Sommerfield, the pen name of Sylvie Fusco, was a hairdresser before she gained fame as a historical romance writer in the 1980s. At a glance, the similarities between Sommerfield and Dailey are striking: both were from small towns and had working class jobs pre-fame, Sylvie’s husband John left his investment banking job to manage her career, and she also had a plagiarism dust-up in the early 90s, which Sommerfield attributed to a researcher gone rogue.

Something that I’ve learned from all of my research is that it’s nearly impossible to piece together a person’s life from headlines and court records, which often only consist of their highest and lowest moments. If Sylvie Sommerfield’s death was truly tragic to the Romantic Times, perhaps they would have concluded that she deserved better than to be a three-paragraph cautionary tale, sloppily crafted from fragments of public knowledge.

Sullivan ends the piece with, “I hope good can come out of this, because Janet was an admired and much loved pioneer of the genre at its infancy, and for a woman who has written so many happy endings for so many people, it’s time she had one of her own at long last.” This line is so discordant with the rest of the article that it truly puzzled me, until I realized that the “happy ending” would likely have to include a separation from Bill.

Bill Dailey was a lot of things: rude, loud, stubborn, and someone who I think I would decidedly not like if I met him in person. But I’m not Janet, I don’t know the inner workings of their marriage, and it’s paternalistic to frame the doting things she has said about Bill— she was consistent in her love and praise of him — in a sinister light to tell a story about Janet’s bad behavior.

Shattered Glass is a 2003 film about Stephen Glass’ career at The New Republic, where he infamously made up sources in order to write fabricated stories. After I watched the film in a college course, I remember telling my professor that the movie was bad because it’s just a retelling of what he did and how he got caught. I wanted to know why he did it.

What I now realize is that why he did it is unknowable, and anything put to screen explaining his bizarre actions would likely be as much of a fabrication as the stories Glass wrote. Sometimes we don’t get the why, and we have to be okay with that.

Bill Dailey died in 2005 from pancreatic cancer, and Janet died in 2013 due to complications from heart surgery. They both got fitting send-offs: Bill orchestrated his own funeral with the Branson acts he helped put on the map, and Janet Dailey made national headlines one last time.

If you’d like to hear more of this story, please tune in to the Reformed Rakes podcast! There are many details about the Daileys’ early life, and reactions to the scandal, that I couldn’t possibly include in one article. Janet Dailey: Part One, and Janet Dailey: Part Two are both out now. I couldn’t link every source due to Substack’s email limit, but all articles are on ReformedRakes.com.

This was fantastic!