Not Your Grandma's Romance Novel

The big 5 publishers have failed us. It's time to stop touting Gen Z as the solution.

“How come Sandra, all of the romance novel cover guys — most of them— have long hair?” Wally Kennedy, host of the morning show AM Philadelphia, asked romance novelist Sandra Kitt. The question is a sharp pivot— Kitt, the first Black romance novelist to be published with Harlequin— had just finished answering a question about the trials of interracial couples in her latest novel, The Color of Love. The year is 1995, and she’s sat slightly apart from three long-haired cover models, reminiscent of the Fabios and John DeSalvos of the day, to discuss why romance novels are so popular with women.

“You do see [the long hair] primarily in the historical novels,” she answered gamely. “I write contemporaries and my heroes tend to have shorter cuts.”

But Kennedy already knew this, having introduced Kitt as a trailblazing author. In an earlier shot, four of her books are displayed where the men on the cover, unaided by prenatal supplements or a wind machine, pose amorously with their counterparts.

The joke, the Fabio in the room, was too strong of a pull for Kennedy to ignore, even though it was clearly irrelevant to Kitt and her books. If by 1995 this joke was tedious, by 2022 it’s downright eye-roll-inducing.

“Picture a romance novel” demands Electric Literature, “Are there heaving bosoms and swaggering poses? Is the word “trashy” one of the first to pop into your mind? If so, your stereotypes are decades out of date.”

Esquire has a similar hook: “If romance novels conjure images of drugstore paperbacks, the ones with Fabio's oiled-up abs on the cover and nothing but florid writing on love making, let me bring you up to speed.”

“I think a youth spent with Fabio as a ubiquitous romance-novel cover model and cultural joke as a dumb hunk who women nonetheless fantasized about forged my general impression of romance novels as fundamentally silly, if hot to some.” declares one of the “romance novel newbies” from Slate’s infamously asinine Bridgerton discussion.

And thus, Wally Kennedy’s wide-eyed, smirking questions about romance novels are posed as sincere, as deserving of a response even decades later. Writers are quick to mention the stigma against romance novels, but equally quick to reinforce it in their patronizing defense. Romance novels are acceptable now, because they’re marketed differently, and because they don’t remind you of your mom or grandma, who enjoy florid writing and fundamentally silly novels.

The New Romance Reader

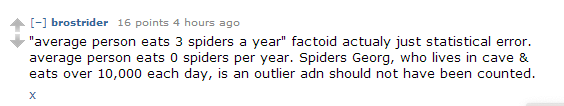

(Colleen Hoover is Spiders Georg)

“A decade ago, the main demographic for romance was women ages 35 to 54. But in the past several years, that has widened to include women 18 to 54, according to Colleen Hoover's publicist Ariele Fredman” cites NPR in Gen Z is driving sales of romance books to the top of bestseller lists. NPR’s article touts BookTok and Gen Z as the source of a new romance boom, of younger, more conscious readers who are unashamed of the stigma that comes with reading romance novels.

Wordsrated, the data analytics company, backs up Fredman’s 18 to 54 statistic, which would seem impressive if it were not for the fact that this song and dance has been done before for millennials. According to Nielsen’s Book Buying Report in 2015, “The fan base is a broader group than you might think, as recent popular titles have welcomed new readers to the genre in the past few years… Romance book buyers are getting younger—with an average age of 42, down from 44 in 2013. This makes the genre’s average age similar to the age for fiction overall. In addition, 44% of these readers are aged 18-44, which includes the coveted Millennial demographic.” [Emphasis my own.]

The early days of the pandemic saw a notable increase in the amount of traditionally published romance book sales, particularly in e-book format, according to NPD. In 2021 Fortune notes the continuing trend, calling romance “literary comfort food” that outsold every other genre except general fiction. The reasoning is that we were so lonely, so unhappy, and so isolated. Of course we would want the comfort of a happily ever after.

But what’s so different about 2022? The rise of BookTok has garnered so much attention as a make-or-break moment for authors, particularly in a world where the big five publishers are no longer spending marketing money on books that aren’t a sure thing. NPR’s article touts Emily Henry and Colleen Hoover as Romance BookTok success stories, but Hoover is an author that has famously outsold the Bible this year. She took up four spots on the Amazon best-selling books of the year, and two spots in the Goodreads Awards Romance category. Hoover is the Spiders Georg of authors, she’s an outlier. It Ends With Us, her biggest hit, masquerades as a romance novel just to gut-punch you with a domestic drama. Any article about romance novels that includes Hoover without caveats is suspect.

Because nobody really understands the algorithm, going viral on TikTok is like winning the lottery. And even after winning this game of chance, I’ve seen authors post about how their viral marketing video didn’t necessarily translate into the sales they were hoping for. For the most part, it’s not just one video on TikTok that makes you a success. You have to clog the algorithm, which is frequently accomplished by traditional marketing methods like a mass distribution of ARCs (Advanced Reader Copies, often sent out for free to reviewers in exchange for a review on their platform) and book boxes. I have never subscribed to Book of The Month, but I can easily list twenty books they’ve sold thanks to the way their relentless marketing campaigns dominate my TikTok feed.

Here’s the rub: Colleen Hoover and Emily Henry are both lead authors. (The definition of “lead author” in traditional publishing is difficult to pin down, but Judith Ivory described it best in 1999: “Any bookseller taking a romance will take that book.”) Hoover and Henry’s viral TikTok books are published by imprints of Simon & Schuster and Penguin Random House respectively— two of the big 5 publishing houses— with all the resources that entail. It’s true that It Ends With Us gained a resurgence on TikTok years after its publishing date, but TikTok alone is not why that book is inescapable. I was in three different airports in three different countries last weekend and both It Ends With Us and It Starts With Us were front and center in every bookshop display. This isn’t just TikTok virality, this is a level of ubiquity on par with The Da Vinci Code.

Or on par with…

Fifty Shades (of Fucked Up)

The Guardian’s recent article, The love boom: why romance novels are the biggest they’ve been for 10 years has a similar thesis to NPR. Romance novels are big now because of Gen Z, who are no longer ashamed of sex, and no longer ashamed to be caught reading romance novels.

I’m a Romance BookTok creator with an account dedicated to vintage romance novels and their cover art, which means I walk an interesting line in speaking to a primarily young audience about books that were released before they were readers. What I’ve learned is that the stigma against romance novels is not just because romance novels are seen as something women enjoy, but because it’s seen as something older women enjoy. In fact, younger readers are just as susceptible to shame as older readers, and they own up to it frequently in their attempts to distance themselves from the romance novels consumed by prior generations. In a video where I talk about the rise of cartoon covers in romance novels, I was overwhelmed with comments about how these covers, which largely have the sexual appeal of a collegiate pamphlet, are much more acceptable to read in public than your classic smutty clinch pose. Sounds like there’s still some shame there, huh?

The reason that romance novels are the biggest that they’ve been in ten years like The Guardian article claims, is that ten years ago, Fifty Shades of Grey reigned supreme. Like It Ends With Us and all things Hoover, Fifty Shades was an outlier. A decade ago, when Hoover gained unexpected success in self-publishing her first novel, EL James was dominating the cultural consciousness. She released her Twilight fanfiction, Master of the Universe, as three largely unedited Grey novels, all of which were runaway hits that were later adapted for the screen.

James and Hoover had different paths, but the similarities are striking. Both James and Hoover were enveloped in traditional publishing after proving their word-of-mouth success: Hoover in the self-publishing world and James in both fanfiction and self-publishing. Hoover sold more books than the Bible this year, and James has reached a level of romance ubiquity that is on par with Fabio. Both James and Hoover have received consistent backlash about how they romanticize abuse through their controlling, alphahole heroes. James wrote fanfiction, and Hoover detractors frequently say she sounds “like a Wattpad author.”

The telling difference is that Fifty Shades of Grey readers were largely assumed to be middle-aged women, as opposed to the Gen Z audiences that are devouring Hoover. The Guardian included Hoover in a glowing article about great strides in romance novels. What did they say about Grey in 2012?

“Literature lovers around the world have released a collective gasp, or perhaps a groan, at the news that the publishing phenomenon Fifty Shades of Grey has become the bestselling book in British history.”

Even when they were complimentary, it was the epitome of damning with faint praise:

“The fact that a middle-aged woman has written it is also often evident… To a huge extent, though, this is the novel's charm. Its innocence and freshness are reflected in its heroine, whose litany of "holy crap!" and "holy Moses", once you can get over the Sarah Palinness of it, are rather endearing. The sole "erotic" thing anyone ever does is bite or play with their bottom lip, and Christian, is, frankly, a bit of a nobber in both senses.”

So Fifty Shades of Grey is corny, but is that so unique? Hoover’s smash-hit It Ends With Us prominently features the main character writing to her childhood hero, Ellen Degeneres, a woman who danced her way out of beloved icon status after years’ worth of damning blind items were made public knowledge. Even when this book was first published in 2016, the letters to Ellen would feel, if not out of touch, then at least a little grating. There’s also the notorious big baby balls quote (read at your own risk) that floats around Twitter with alarming regularity. But Hoover’s readers, as we’re frequently told, are young, and that’s why she’s leading the new frontier of romance, despite not even really being a romance author.

Daunt(less)

The breathless prostheletyzing about how Gen Z is turning this ship around treats BookTok success as a driving industry force instead of an outlier for a few lucky authors, which is convenient for publishers who can then tout TikTok’s notoriously racist algorithm as the reason why authors of color aren’t selling as much. But as many BookTokers have pointed out, Tracy Deonn’s Bloodmarked, the follow-up to her BookTok hit Legendborn, was exceedingly difficult to find in Barnes & Noble on the day of its release. Like It Ends With Us, Bloodmarked is also published under an imprint of Simon & Schuster, so there should be a major push to get it onto shelves and into the hands of eager readers.

But Barnes & Noble itself could also be the problem. Purchased a few years ago by Elliott Management Corporation, the hedge fund that also owns Waterstones in the UK, Barnes & Noble is now under the careful eye of CEO James Daunt, whose claim to fame is restructuring individual Waterstones to mimic the feel of the independent bookstores they’ve helped put out of business. The “exercis[ing] taste in the selection of new titles” as he calls it, has resulted in a decision that Barnes & Noble will limit the stock of hardcovers written by authors that haven’t proven their success. Deonn notably doesn’t fall into the affected category, but the decision seems primed to disproportionately hurt authors of color. Any CEO that calls these legitimate concerns “jumping at shadows” and balks at raising the minimum wage for his booksellers does not have the best interest of marginalized communities at heart. This is not a problem you can lay at BookTok’s feet.

Daunt’s minimalist ethos is also bad news not just for authors, but for the romance book section itself. Individual stores have the power to choose what books they stock, and any store without a romance advocate, like the two Waterstones I’ve painstakingly searched in Glasgow, will do without. Instead, you’ll find the big romance trade paperbacks, The Love Hypothesis and It Starts With Us, mixed in with general fiction.

The early pandemic boom saw an increase in traditionally published e-book sales, like for Lisa Kleypas’s Chasing Cassandra, according to NPD. The increase now, according to The Guardian, is for the trade paperbacks that younger readers are buying in droves. But I don’t think this is because younger readers don’t like Kleypas - Kleypas has been a lead author for Avon since the 90s, and is continuously one of the first names people recommend when they say “historical romance.” But you can’t sell Kleypas, with her billowing gowns and saucy stepbacks, as anything other than a genre romance novelist, so her shelf space isn’t necessarily guaranteed in James Daunt’s world.

The big five publishers are no longer advocating for genre fiction on the scale that they used to. Mass market paperbacks, the bread and butter of genre fiction, have been cast aside for the larger and more expensive trade paperbacks that can easily masquerade as literary fiction. The door into Waterstones and Barnes & Noble is closing, wealthy publishers are asking their midlist authors to do their own marketing, and the new frontier of romance novels that look like romance novels lies firmly in the self-publishing realm.

Your grandma’s romance novels [derogatory] were written by people who were paid a living wage, and who could depend on their publishers for a modicum of support. That's not the case anymore, so where are the genre romance trend pieces about that?

Your Grandma’s Romance Novels (Revisited)

Like Kitt in 1995, authors and readers are continuously trying to escape the Fabio of it all. Fabio hasn’t graced a romance novel cover since the 90s, but he’s become a sort of symbol of how people feel about romance readers, particularly the older ones. All flash and cartoonish sexuality, no substance.

I’m not about to pretend that romance novels published before 2000 are a bastion of progressivism and are beyond critique, but by the way people talk about them I think they would be surprised at what they would find between the pages.

There’s a comforting lie that people tell themselves about how progress is linear, as evidenced by Book Riot’s article The History of Consent in Romance Novels. The thesis of the article is that our ideas about the necessity of consent has fundamentally changed, and that we can track that progress through romance novel publishing. To prove the point, the piece is littered with factual inaccuracies (which I’ve picked apart here), but it also treats historical bodice rippers as the only type of romance novels that were being published before the 90s.

Vivian Stephens, the founder of the RWA and influential editor at Dell and Harlequin, opened the door for many authors of color in contemporary romance in the early 1980s. Sandra Kitt’s groundbreaking first novel with Harlequin was published under Stephens's editorial influence.

What Stephens also did, according to this Texas Monthly article, was update contemporary category romance novels so that they were more explicit in their depiction of sex.

“Authors like Kathleen Woodiwiss had already shown there was a demand for steamier fiction with the historical blockbuster The Flame and the Flower, in 1972, but Stephens wanted to update the model with women whose experiences more closely resembled her own.”

I have yet to read a book that Stephens edited where the sex scenes weren’t consensual. This not only messes up Book Riot’s timeline, but it erases Stephens’s legacy to create a false now vs then, which is a panacea to people who don’t want to acknowledge how traditional publishing continues to fail authors and readers in 2022.

As of this writing, Vivian Stephens is 90 years old. She has no children, but she’s definitely in that much-derided grandma category, a person we are no longer writing romance novels for.

There are other ways where touted improvements in modern romance novels are actually a lot murkier than they seem. A common criticism of modern romance is that there’s a lack of discussion of safe sex, and no option for abortion for the “surprise pregnancy” plots. You’d think it would be worse in the 80s and 90s, right? Not so much.

In Judith Ivory’s historical romance novel Black Silk, published in 1991, the hero, Graham, waxes poetic about his mission to find condoms:

”If a gentleman bought these conveniences at a more sordid establishment, he might have to use the dirty name, c——m; even the most salacious literature never wrote the word out. Graham wasn’t even sure how to spell it. Condim? Condom? Condum? But he knew how to say it, in several languages, in a dozen euphemisms, up and down the class system, on and off the Continent.”

The pregnancy plot in Valerie Vayle’s historical romance Nightfire, published in 1986, is delivered with compassion. The heroine, Simonne, not only gets pregnant by a man who isn’t the main love interest, but she spends over half the book as his mistress. I can practically hear Goodreads reviewers, who absolutely loathe a promiscuous heroine, howling in rage at this, as though it’s a cardinal sin and not something that happens in life. You fuck someone for a while, then you find someone better.

But when Simonne gets pregnant, she considers an abortion. Her love interest, Sasha, who is also a doctor, is too scared to give her one. He says that at this point he’d have to result to surgical methods, and he’s not sure Simonne would survive.

Later, when Sasha is a prisoner during the French Revolution, he learns how to give non-surgical abortions to patients in need. He’s motivated by safety and care, and Vayle avoids the common historical romance “tea-induced abortion” plotline to be more frank and empathetic to Sasha’s calculated ethics.

I have countless other examples, but the crux of my point is that Not Your Grandma’s Romance Novel is often touted by people that have no interest in the history of romance, or even worse, a vested interest in painting modern romance publishing in a more flattering light than it deserves. It’s an extension of the stigma we say that we’re working against, and it’s particularly unkind in a genre where most readers’ origin stories begin with, “I stole a book from my mom.”

Back in 1995, after interviewing Kitt and the cover models, Wally Kennedy takes listener calls on-air. The last call is from an old woman.

“Hello Mr. Kennedy. I’m seventy-five years old and I love romance novels. I sit back for an hour or whatever it takes and I’m young again, and I’m flirting with the men with hairy chests and all that stuff— and I know it can never happen to me, but at least for a little while I’m young again. And I’m in love again. And it keeps me alive— that’s all I have to say, sweetheart.”

If we aren’t still writing romance novels for people like her, then I want no part of it.

I'm not gonna lie, that last paragraph made me cry. Because I am almost completely certain, that this will be me. I am 18 now, but I just know that my love for (historical) romance novels will stay with me.

I didn't know that historical romance could be consensual and empathetic! I just believed what everyone regurgitated, maybe I'll check them out! This was such an interesting read, thank you!